Stories from elders speak of a time when the world went crooked.

For Chicago, that bend began in 1696, the year King Louis XIV decided he was tired of losing control of a continent he had never seen.

The fur trade had slipped out of France’s grasp like water through open fingers. Traders were vanishing into the interior of the continent. These men had no patience for rules, no interest in taxes, and no fear of priests. They smuggled brandy under moonlight, made deals in languages the Crown couldn’t understand, and grew rich on pelts that never passed a French ledger.

Louis XIV, who preferred order the way a wolf prefers flesh, responded by shuttering trading posts across New France.

He thought he could choke the wilderness into obedience with rules written an ocean away.

Instead, he cracked the continent open.

Because the moment the Crown tried to block the rivers, the rivers simply chose new paths. Traders went underground. Indigenous nations forged their own alliances. And the Chicago Portage, quiet, narrow, half mud and half memory, became a shadow route for every kind of bargain the king could not control.

The marsh learned new kinds of footsteps: hurried ones, secret ones, guilty ones.

It liked none of them.

But the land is patient.

It watches.

It remembers who moves through it, and who stays.

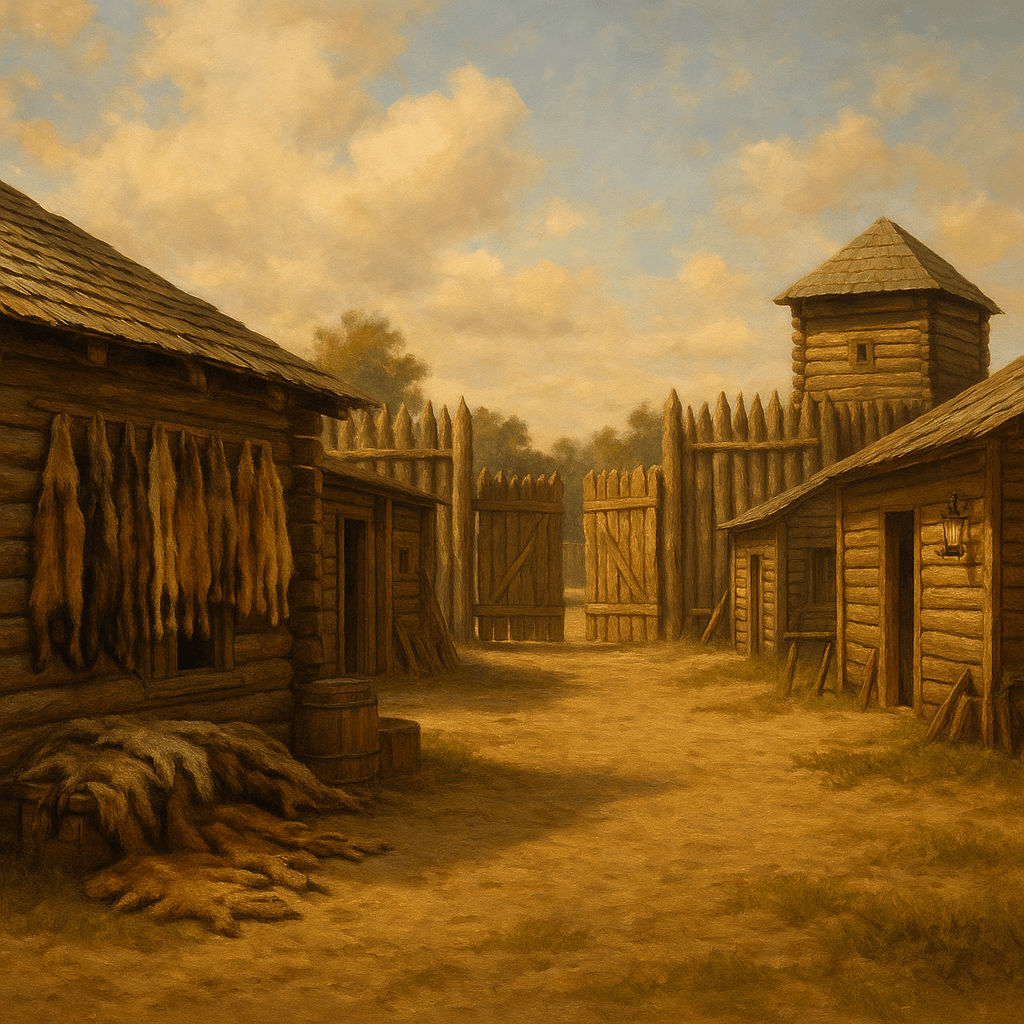

As the French slipped in with contraband brandy and whispered deals, something else was forming along the edges of the marsh. Each winter, when the rivers froze and the interior clenched its icy fist, voyageurs and Jesuit priests drifted toward the Portage for shelter. They built rough cabins, bare wooden ribs leaning into the wind, leaving behind the first faint traces of European presence along the river’s bend. Enough to leave smoke in the air, but never enough to leave a claim.

Chicago became a place where men wintered, not lived. A station. A stopover. A waystation for travelers who needed the land more than it needed them. Priests prayed over thin blue flames. Traders huddled under furs, whispering rumors into the cold. And when the thaw returned, they vanished, leaving nothing behind but footprints and the skeletal remains of their makeshift shelters.

But while the French used Chicago out of necessity, another people called it home.

By the early 1700s, the Potawatomi were not merely present; they were the pulse, the law, the order of the marsh. Their villages glowed along the riverbanks like steady flames, warm where the French burned bright and brief. Their families harvested wild rice in the wetlands, fished the river mouth, and moved through the tallgrass with the ease of those claimed by the land.

The Portage was theirs.

The trade routes were theirs.

The decisions about who passed, who traded, who lingered, they made those choices, not the French, not the priests, and certainly not the Crown.

To the Potawatomi, the Chicago Portage wasn’t a shortcut.

It was an inheritance, the crossroads the continent leaned on.

And they guarded it with eyes that missed nothing. Travelers learned quickly that safe passage wasn’t granted by European maps but by Potawatomi diplomacy: a gift here, a promise there, a respectful bow.

Chicago didn’t become Potawatomi by accident.

It became Potawatomi because they understood the land, spoke its languages, and shaped its stories long before foreign boots pressed into the marsh.

As French winter cabins rose and fell with the seasons, the Potawatomi presence remained strong and confident, rooted in the earth, as rivers settle into their ancient beds.

Far to the north and west, the Meskwaki tribe, called the Fox by the French, refused to bow to anyone. They controlled the land that the voyageurs needed to reach the Mississippi. They blocked French ambition with a single word: No.

France could tolerate many insults.

Defiance was not one of them.

So the French gathered allies: Potawatomi, Miami, Illinois, Kickapoo, each with its own history, its own grievances, and its own reasons to fight. The war that followed spread through the Great Lakes like wildfire, searching for dry grass.

Chicago wasn’t a battlefield, but it felt the pressure.

Refugees slipped through the Portage with eyes full of smoke and ash.

Warriors passed silently, faces painted, arrows sharpened.

Traders walked faster, glancing over their shoulders, unsure who waited beyond the next bend.

The marsh absorbed every secret, every whisper, every tremor.

And when the Fox made their final stand in 1730, surrounded on an Illinois bluff, their fort was crushed under the weight of French guns and tribal alliances. The echo rolled toward Chicago like a warning carried on cold wind.

After the Fox Wars simmered out, Chicago fell into a strange stillness.

Potawatomi villages thrummed with life once more.

French traders drifted through like ghosts, laughing loudly to disguise the worry beneath their ribs.

Jesuit priests scolded voyageurs over sin, liquor, and “scandalous unions” that flourished in the shadows.

The French brought eau-de-vie, firewater that burned hotter than any ceremonial drink. It frayed tempers, stirred violence, loosened tongues that should have stayed still. Some became dependent, caught in a cycle the French understood too well and exploited even better.

Firewater didn’t just scorch Indigenous throats.

It scorched lives.

Elders spoke of hunters once steady and clear-eyed, now stumbling through villages fogged by drink. Families felt it. Alliances strained under it. The land itself seemed to flinch whenever another barrel appeared.

For some, firewater became a hunger that never stopped gnawing, a weapon that needed no blade to wound.

And the Portage grew tense, a narrow hallway where every traveler looked over their shoulder.

The marsh was quiet.

But it was not peaceful.

It was waiting.

Because everyone felt it in the air:

France was cracking.

Britain was prowling.

And the land between them, the land Chicago sat upon, would soon become the hinge on which the world turned.

By the early 1750s, distant thunder rumbled across the continent. Forts fell.

Alliances fractured.

Leave a comment